Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (39)

- Monotypic

Carles Carboneras and Guy M. Kirwan

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated February 8, 2016

Text last updated February 8, 2016

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Asturian | Gansu picucurtiu |

| Basque | Antzara mokolaburra |

| Bulgarian | Късоклюна гъска |

| Catalan | oca de bec curt |

| Croatian | kratkokljuna guska |

| Czech | husa krátkozobá |

| Danish | Kortnæbbet Gås |

| Dutch | Kleine rietgans |

| English | Pink-footed Goose |

| English (United States) | Pink-footed Goose |

| Estonian | lühinokk-hani |

| Faroese | Íslandsgás |

| Finnish | lyhytnokkahanhi |

| French | Oie à bec court |

| French (Canada) | Oie à bec court |

| Galician | Ganso de bico curto |

| German | Kurzschnabelgans |

| Greek | Βραχύραμφη Χήνα |

| Hebrew | אווז קצר-מקור |

| Hungarian | Rövidcsőrű lúd |

| Icelandic | Heiðagæs |

| Italian | Oca zamperosee |

| Japanese | コザクラバシガン |

| Latvian | Īsknābja zoss |

| Lithuanian | Trumpasnapė žąsis |

| Norwegian | kortnebbgås |

| Polish | gęś krótkodzioba |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Ganso-de-bico-curto |

| Romanian | Gâscă cu cioc scurt |

| Russian | Короткоклювый гуменник |

| Serbian | Kratkokljuna guska |

| Slovak | hus krátkozobá |

| Slovenian | Kratkokljuna gos |

| Spanish | Ánsar Piquicorto |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Ganso Piquicorto |

| Spanish (Spain) | Ánsar piquicorto |

| Swedish | spetsbergsgås |

| Turkish | Küçük Tarla Kazı |

| Ukrainian | Гуменник короткодзьобий |

Anser brachyrhynchus Baillon, 1834

PROTONYM:

Anser Brachyrhynchus

Baillon, 1834. Mémoires de la Société Royale d'Émulation d'Abbeville (1833), p.74.

TYPE LOCALITY:

Abbeville, lower Somme River, France.

SOURCE:

Avibase, 2024

Definitions

- ANSER

- anser

- brachyrhynchus / brachyrrhynchus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

UPPERCASE: current genus

Uppercase first letter: generic synonym

● and ● See: generic homonyms

lowercase: species and subspecies

●: early names, variants, misspellings

‡: extinct

†: type species

Gr.: ancient Greek

L.: Latin

<: derived from

syn: synonym of

/: separates historical and modern geographic names

ex: based on

TL: type locality

OD: original diagnosis (genus) or original description (species)

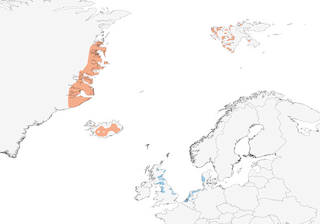

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding

Distribution of the Pink-footed Goose