Lesser Yellowlegs Tringa flavipes Scientific name definitions

- VU Vulnerable

- Names (63)

- Monotypic

Text last updated February 28, 2014

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Kleingeelpootruiter |

| Arabic | طيطوي صفراء الساق صغيرة |

| Asturian | Chibibí patimariellu pequeñu |

| Azerbaijani | Sarıayaq ilbizcüllütü |

| Basque | Kuliska hankahori txikia |

| Bulgarian | Малък жълтоног водобегач |

| Catalan | gamba groga petita |

| Chinese | 小黃腳鷸 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 小黃腳鷸 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 小黄脚鹬 |

| Croatian | kratkokljuna prutka |

| Czech | vodouš žlutonohý |

| Danish | Lille Gulben |

| Dutch | Kleine geelpootruiter |

| English | Lesser Yellowlegs |

| English (United States) | Lesser Yellowlegs |

| Estonian | kollajalg-tilder |

| Finnish | keltajalkaviklo |

| French | Petit Chevalier |

| French (Canada) | Petit Chevalier |

| French (France) | Chevalier à pattes jaunes |

| French (French Guiana) | Chevalier à pattes jaunes |

| Galician | Bilurico patiamarelo pequeno |

| German | Gelbschenkel |

| Greek | Μικρός Κιτρινοσκέλης |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Bekasin janm jòn |

| Hebrew | ביצנית צהובת-רגל |

| Hungarian | Sárgalábú cankó |

| Icelandic | Hrísastelkur |

| Indonesian | Trinil kaki-kuning |

| Italian | Totano zampegialle minore |

| Japanese | コキアシシギ |

| Latvian | Mazais dzeltenstilbis |

| Lithuanian | Geltonkojis tulikas |

| Norwegian | gulbeinsnipe |

| Polish | brodziec żółtonogi |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | maçarico-de-perna-amarela |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Perna-amarela-pequeno |

| Romanian | Fluierar mic cu picioare galbene |

| Russian | Желтоногий улит |

| Serbian | Mali žutonogi sprudnik |

| Slovak | kalužiak žltonohý |

| Slovenian | Mali rumenonogi martinec |

| Spanish | Archibebe Patigualdo Chico |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Pitotoy Chico |

| Spanish (Chile) | Pitotoy chico |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Patiamarillo Menor |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Zarapico patiamarillo chico |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Patas Amarillas Menor |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Patiamarillo Menor |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Playero Patas Amarillas Menor |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Patamarilla Menor |

| Spanish (Panama) | Patiamarillo Menor |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Pitotoi chico |

| Spanish (Peru) | Playero Pata Amarilla Menor |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Playero Guineílla Menor |

| Spanish (Spain) | Archibebe patigualdo chico |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Playero Menor Patas Amarillas |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Tigüi-Tigüe Chico |

| Swedish | mindre gulbena |

| Turkish | Küçük Sarıbacak |

| Ukrainian | Коловодник жовтоногий |

| Zulu | unomlenzophuzi |

Tringa flavipes (Gmelin, 1789)

Definitions

- TRINGA

- flavipes

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

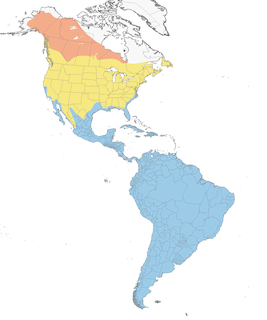

This common, medium-sized shorebird is usually recognized by its long, bright-yellow legs, long neck, graceful stride, and distinctive tu tu call. In summer, breeders are conspicuous residents of open woodlands, meadows, and muskegs in the boreal zone from northwestern Alaska to central Québec. In winter, they frequent a wide variety of wetland types throughout Central and South America, the West Indies, and the southern United States.

Lesser Yellowlegs usually travel in small, loosely structured flocks, but concentrations of thousands are seen at preferred foraging sites during migration and at their main wintering areas in Suriname. The species is a widespread migrant in North America, with primary movement through the interior (spring and fall) and along the Atlantic Coast (fall). Across their wintering range and in the southern portion of their breeding range, Lesser Yellowlegs are often found in the company of their larger congener, the Greater Yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca). With a little practice, these two similar species can be readily distinguished by overall size, bill proportions, and voice.

Most research on Lesser Yellowlegs has described diet and habitat associations of nonbreeding birds (e.g., Baldassarre and Fischer 1984, Skagen and Knopf 1994a). These studies have provided important baseline information on this species' habitat requirements during migration. Other studies have investigated timing and energetics of migration at stopover sites (e.g., McNeil and Cadieux 1972a), trends in fall population size on the Atlantic coast (Howe et al. 1989), and response of the species to wetlands management (e.g., Rundle and Fredrickson 1981, Weber and Haig 1996).

Information on breeding biology is based on a few descriptive studies conducted in the early 1900s in Alberta by Fletcher Street (Street 1923), William Rowan (Rowan 1929), and Thomas Randall (in Bannerman 1961), and a recent study with marked individuals in Alaska (L. Tibbitts unpubl.). These studies indicate that Lesser Yellowlegs are socially monogamous, return to the same general breeding areas, and exhibit low mate fidelity across years. Soon after spring arrival on breeding areas, males begin to perform their distinctive undulating flight displays over nesting and foraging sites. Display activity abates once nests are initiated, and both parents take turns incubating the four-egg clutch. A well-known trait of Lesser Yellowlegs is their vigorous defense of nests and chicks. This behavior was aptly described by Rowan (Rowan 1929) when he stated, “they will be perched there as though the safety of the entire universe depended on the amount of noise they made.” This species provides biparental care to its precocial young but females tend to depart breeding areas before chicks can fly, thus leaving males to defend the young until fledging.

Lesser Yellowlegs were avidly sought by sport and market hunters in the late 1800s. High harvest levels during this period were partly due to this species' propensity to return and hover above wounded flockmates, making them easy targets for gunners. Many observers of the day speculated that populations declined during this period but subsequently recovered once hunting in the USA was outlawed. As recently as 1991, however, several thousand Lesser Yellowlegs were still being shot annually for sport in the Caribbean, and this shooting continues. Recent (2012) estimates suggest that 7,000-15,000 individuals may be shot each fall in migration at wetlands constructed by shooting clubs on Barbados; perhaps half that many may be shot each fall on Guadeloupe and Martinique, with a potentially significant take also on wintering grounds in Suriname and Guyana. See details in Clay et al. (2012). Clearly this is a significant threat to the species and requires continued monitoring.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding