Black-winged Kite Elanus caeruleus Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (65)

- Subspecies (4)

Alan C. Kemp, Guy M. Kirwan, Jeffrey S. Marks, Anna Motis, and Ernest Garcia

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated February 24, 2017

Text last updated February 24, 2017

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Blouvalk |

| Arabic | حدأة سوداء الجناح |

| Armenian | Սևաթև ցին |

| Asturian | Elanu común |

| Azerbaijani | Bozumtul çalağan |

| Bangla | কাপাসি চিল |

| Bangla (Bangladesh) | কাপাসি চিল |

| Bangla (India) | কাপাসি |

| Basque | Elano urdina |

| Bulgarian | Пепелява каничка |

| Catalan | elani comú |

| Chinese | 黑翅鳶 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 黑翅鳶 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 黑翅鸢 |

| Croatian | crnokrila lunja |

| Czech | luněc šedý |

| Danish | Blå Glente |

| Dutch | Grijze wouw |

| English | Black-winged Kite |

| English (India) | Black-winged Kite (Black-shouldered Kite) |

| English (Kenya) | African Black-shouldered Kite |

| English (United States) | Black-winged Kite |

| Estonian | hõbehaugas |

| Finnish | liitohaukka |

| French | Élanion blanc |

| French (Canada) | Élanion blanc |

| Galician | Peneireiro cinsento |

| Georgian | ფრთაშავი ლურჯი ძერა |

| German | Gleitaar |

| Greek | Έλανος |

| Gujarati | કપાસી |

| Hebrew | דאה שחורת-כתף |

| Hindi | कपासी चील |

| Hungarian | Kuhi |

| Icelandic | Völsungur |

| Indonesian | Elang tikus |

| Italian | Nibbio bianco |

| Japanese | カタグロトビ |

| Kannada | ರಾಮದಾಸ ಹದ್ದು |

| Korean | 검은어깨매 |

| Latvian | Melnplecu klija |

| Lithuanian | Palšasis peslys |

| Malayalam | വെള്ളി എറിയൻ |

| Marathi | कापशी घार |

| Nepali (Nepal) | मुसे चील |

| Norwegian | svartvingeglente |

| Odia | ଧୁଲ ଛଞ୍ଚାଣ |

| Persian | کورکور بال سیاه |

| Polish | kaniuk |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Peneireiro-cinzento |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Peneireiro-cinzento |

| Punjabi (India) | ਚਿੱਟੀ ਇੱਲ |

| Romanian | Gaie cenușie |

| Russian | Дымчатый коршун |

| Serbian | Bela lunja |

| Slovak | luniak sivý |

| Slovenian | Sinji lebduh |

| Spanish | Elanio Común |

| Spanish (Spain) | Elanio común |

| Swedish | svartvingad glada |

| Telugu | అడవి రామదాసు |

| Thai | เหยี่ยวขาว |

| Turkish | Ak Çaylak |

| Ukrainian | Шуліка чорноплечий |

| Zulu | udemezane |

Elanus caeruleus (Desfontaines, 1789)

PROTONYM:

Falco caeruleus

Desfontaines, 1789. Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences. Avec les Mémoires de Mathématique & de Physique (1787), p.503 pl.15.

TYPE LOCALITY:

Algiers.

SOURCE:

Avibase, 2024

Definitions

- ELANUS

- elanus

- caeruleus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

UPPERCASE: current genus

Uppercase first letter: generic synonym

● and ● See: generic homonyms

lowercase: species and subspecies

●: early names, variants, misspellings

‡: extinct

†: type species

Gr.: ancient Greek

L.: Latin

<: derived from

syn: synonym of

/: separates historical and modern geographic names

ex: based on

TL: type locality

OD: original diagnosis (genus) or original description (species)

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding

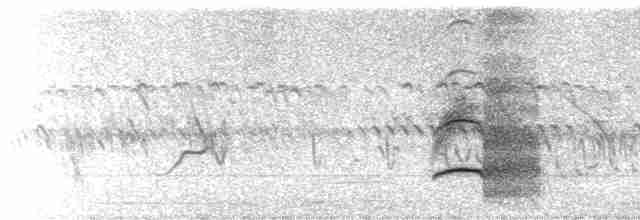

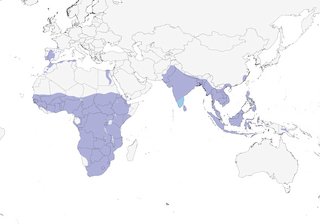

Distribution of the Black-winged Kite