Black Stork Ciconia nigra Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (63)

- Monotypic

Andrew Elliott, David Christie, Ernest Garcia, and Peter F. D. Boesman

Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

Text last updated November 30, 2018

Text last updated November 30, 2018

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Grootswartooievaar |

| Albanian | Lejleku i zi |

| Arabic | لقلق اسود |

| Armenian | Սև արագիլ |

| Assamese | কালশৰ |

| Asturian | Cigüeña prieta |

| Azerbaijani | Qara leylək |

| Bangla (India) | কালোজঙ্ঘা |

| Basque | Zikoina beltza |

| Bulgarian | Черен щъркел |

| Catalan | cigonya negra |

| Chinese | 黑鸛 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 黑鸛 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 黑鹳 |

| Croatian | crna roda |

| Czech | čáp černý |

| Danish | Sort Stork |

| Dutch | Zwarte ooievaar |

| English | Black Stork |

| English (United States) | Black Stork |

| Estonian | must-toonekurg |

| Finnish | mustahaikara |

| French | Cigogne noire |

| French (Canada) | Cigogne noire |

| Galician | Cegoña negra |

| Georgian | შავი ყარყატი (იშხვარი) |

| German | Schwarzstorch |

| Greek | Μαύρος Πελαργός |

| Gujarati | કાળો ઢોંક |

| Hebrew | חסידה שחורה |

| Hindi | सुरमल |

| Hungarian | Fekete gólya |

| Icelandic | Kolstorkur |

| Italian | Cicogna nera |

| Japanese | ナベコウ |

| Kannada | ಕರಿ ಕೊಕ್ಕರೆ |

| Korean | 먹황새 |

| Ladakhi | གཞད་ནག |

| Latvian | Melnais stārķis |

| Lithuanian | Juodasis gandras |

| Malayalam | കരിമ്പകം |

| Mongolian | Хар өрөвтас |

| Nepali (India) | कालो सारस |

| Nepali (Nepal) | कालो गरुड |

| Norwegian | svartstork |

| Persian | لک لک سیاه |

| Polish | bocian czarny |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Cegonha-preta |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Cegonha-preta |

| Punjabi (India) | ਕਾਲਾ ਲਮਢੀਂਗ |

| Romanian | Barză neagră |

| Russian | Чёрный аист |

| Serbian | Crna roda |

| Slovak | bocian čierny |

| Slovenian | Črna štorklja |

| Spanish | Cigüeña Negra |

| Spanish (Spain) | Cigüeña negra |

| Swedish | svart stork |

| Telugu | నల్ల కొంగ |

| Thai | นกกระสาดำ |

| Turkish | Kara Leylek |

| Ukrainian | Лелека чорний |

| Zulu | unowanga |

Ciconia nigra (Linnaeus, 1758)

PROTONYM:

Ardea nigra

Linnaeus, 1758. Systema Naturæ per Regna Tria Naturæ, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata 1, p.142.

TYPE LOCALITY:

Northern Europe; restricted type locality, Sweden.

SOURCE:

Avibase, 2024

Definitions

- CICONIA

- ciconia

- nigra

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

UPPERCASE: current genus

Uppercase first letter: generic synonym

● and ● See: generic homonyms

lowercase: species and subspecies

●: early names, variants, misspellings

‡: extinct

†: type species

Gr.: ancient Greek

L.: Latin

<: derived from

syn: synonym of

/: separates historical and modern geographic names

ex: based on

TL: type locality

OD: original diagnosis (genus) or original description (species)

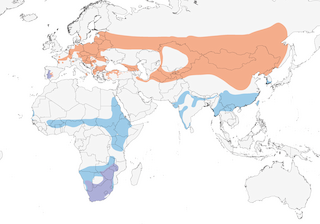

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding

Distribution of the Black Stork