Australasian Grass-Owl Tyto longimembris Scientific name definitions

Text last updated March 6, 2016

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Oostelike Grasuil |

| Bangla (India) | ঘাস পেঁচা |

| Bulgarian | Азиатска ливадна сова |

| Catalan | òliba camallarga oriental |

| Chinese | 草鴞 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 草鴞 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 草鸮 |

| Croatian | travnjačka kukuvija |

| Czech | sova proměnlivá |

| Danish | Græsslørugle |

| Dutch | Oosterse grasuil |

| English | Australasian Grass-Owl |

| English (AVI) | Eastern Grass Owl |

| English (Hong Kong SAR China) | Eastern Grass Owl |

| English (United States) | Australasian Grass-Owl |

| Estonian | padu-loorkakk |

| Finnish | aasianruohopöllö |

| French | Effraie de prairie |

| French (Canada) | Effraie de prairie |

| German | Graseule |

| Indonesian | Serak padang |

| Japanese | ヒガシメンフクロウ |

| Kannada | ಹುಲ್ಲುಗಾಡು ಗೂಬೆ |

| Korean | 가면올빼미 |

| Malayalam | പുൽമൂങ്ങ |

| Nepali (Nepal) | घाँसे लाटोकोसेरो |

| Norwegian | engslørugle |

| Polish | płomykówka długonoga |

| Russian | Травяная сипуха |

| Serbian | Australazijska livadska kukuvija |

| Slovak | plamienka dlhonohá |

| Spanish | Lechuza Patilarga |

| Spanish (Spain) | Lechuza patilarga |

| Swedish | orientgräsuggla |

| Thai | นกแสกทุ่งหญ้า |

| Turkish | Doğu Çayır Baykuşu |

| Ukrainian | Сипуха східна |

Tyto longimembris (Jerdon, 1839)

Definitions

- TYTO

- longimembris

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

Identification

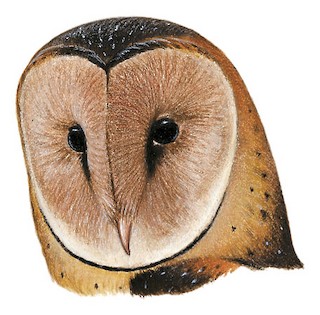

Male 32–36 cm, 265–375 g (Australia), 360 g (Philippines); female 35–38 cm, 320–450 g (Australia), 582 g (Philippines); wingspan 112 cm. Medium-sized Tyto with variable plumage (1). Male dark brown and golden-buff above with some small white spots; facial disc and underparts contrastingly whitish, tinged orange-buff, underparts with sparse blackish dots; flight feathers barred dark, with golden-buff patch at base of primaries ; tail pale, barred dark; eyes dark. Darker than sympatric races of T. alba; generally not so dark as T. capensis. Female as male, or with darker face and underparts. Juvenile resembles adult female, or darker. Australian birds (“walleri”) slightly buffier and on average with more dorsal and ventral spotting, could be confused with light-morph T. novaehollandiae; race chinensis entirely suffused tawny-buff , but some paler; pithecops larger, with some buff suffusion; <em>amauronota</em> like nominate, but slightly larger, upperparts more greyish, buff areas more yellowish, tail bars wider, female and juvenile with facial disc washed vinaceous-brown; papuensis upperparts plainer, darker grey with narrow white shaft streaks, not spots (but some nominate also with streaks), size approaching or equalling pithecops and amauronota; type (adult male) of baliem described as having upperparts much darker than papuensis and extending to two dark patches on sides of neck, possibly averages smaller.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Closely related to T. capensis, with which often considered conspecific. Variation within species poorly understood, owing to rarity of specimens from whole range. Race pithecops sometimes included in chinensis, but appears to be valid. Of several other forms previously separated subspecifically, walleri (from Sulawesi, C Lesser Sundas and N & E Australia), maculosa (SW Australia) and oustaleti (New Caledonia and, at least formerly, Fiji) now regarded as synonyms of nominate, although Australian walleri perhaps warrants recognition on basis of plumage differences and sexual dimorphism; SE China (Guangxi Zhuang and Guangdong) population proposed as race melli, but better merged with chinensis; chinensis itself sometimes included in pithecops, but probably better retained as separate race; baliem (from Baliem Valley, in WC New Guinea) sometimes recognized, but barely distinguishable from papuensis and here subsumed within it. Five subspecies recognized.Subspecies

Tyto longimembris longimembris Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Tyto longimembris longimembris (Jerdon, 1839)

Definitions

- TYTO

- longimembris

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Tyto longimembris chinensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Tyto longimembris chinensis Hartert, 1929

Definitions

- TYTO

- longimembris

- chinense / chinensis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Tyto longimembris pithecops Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Tyto longimembris pithecops (Swinhoe, 1866)

Definitions

- TYTO

- longimembris

- pithecops

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Tyto longimembris amauronota Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Tyto longimembris amauronota (Cabanis, 1872)

Definitions

- TYTO

- longimembris

- amauronota / amauronotus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Tyto longimembris papuensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Tyto longimembris papuensis Hartert, 1929

Definitions

- TYTO

- longimembris

- papuanus / papuense / papuensis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

General Habitat

Grassland , both tall grass jungle and open grassland, paperbark (Melaleuca) savanna, marshes , floodplains and heathland, particularly when undisturbed by human activity, but also cultivated and cleared areas, including cane fields, and even wheat crops (4); in Australia, recently young pine plantations. In many regions, prefers grassy hillsides with thick cover and mid-mountain grassland to c. 2500 m. In Australia apparently 2 main populations: one coastal in marshy heaths and swampy tussock grassland, other inland on floodplains, frequenting treeless tussock grassland and swampy depressions containing areas of rushes, sedges and lignum (Muehlenbeckia), also flooded bore drains and natural mound springs (5, 6). Normally perches on ground, but recent Australian observations of birds perching on tops of young pine trees.

Movements and Migration

Generally sedentary throughout much of range, with some post-breeding dispersal of juveniles. Earlier reports of migration in China and Philippines subsequently attributed to winter breeding activities in former country and occasional flocking in latter. Records of vagrancy within Australia explained by general nomadism and dispersal of inland birds when favourable breeding and food conditions terminate (7), but such movements may also involve some coastal birds, particularly juveniles; N Australian populations possibly not permanent, but result of population explosions in interior; vagrancy elsewhere in Australia probably represents post-breeding dispersal of juveniles, usually coastward, including offshore islands, with nominate race recorded in SE & SW Australia, Palm Is and Magnetic I off Queensland, and Torres Strait islands. The few records from Indonesia, New Caledonia and Fiji (Viti Levu) may be of inland Australian birds, which are more likely to wander such distances; although it has been suggested that records from some of these islands indicate resident or former resident populations, it is not known if breeding has occurred on any of them. In E New Guinea normally found above 2500 m, but sometimes down to c. 400 m, and record of two birds from SE lowlands may represent vagrancy of nominate race from N Australia. Recent observations of dark Tyto owls on several Fijian islands may have included present species, but unconfirmed, and probably T. alba although no dark morph of latter known there. Recorded (chinensis) as possible vagrant to Hong Kong, but probably captive escapes; also, May 1975 record from Iriomote, S Ryukyu Is, Japan, said to be pithecops but could be amauronota (specimen lost).

Diet and Foraging

Specialized rodent-hunter in some areas; pellets collected at nests in NW Thailand consisted mostly of remains of murid rodents (2, 8); in Australia, Mus and Rattus commonly taken (7), but also small dasyurid marsupials (Sminthopsis, Planigale), ground birds such as buttonquails (Turnix) and Brown Quail (Synoicus ypsilophorus) (9), reptiles, frogs, and large insects such as grasshoppers (Saltatoria), locusts (Acrididae) and cicadas (Cicadidae). Unlike T. alba, hunts entirely by low, quartering flight, with glides and hovers, similar to harriers (Circus), plunging head-first into grass. As with T. capensis, hunting begins earlier than T. alba and finishes later; in Australia, this pattern found in situations of stress after inland rodent plagues, when hunting began c. 1 hour before dusk and continued to mid-morning. Although rarely seen unless flushed, in NE Australia plagues of e.g. long-haired rats (Rattus villosissimus) and cane rats (R. sordidus) may result in relatively large concentrations of this species, often mixed with T. alba, T. novaehollandiae and other raptors. When rat numbers crash, many owls starve.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

In Asia noted to produce screech similar to that made by T. alba, but generally considered more silent. Various calls recorded in Australia: hissing scream in flight over breeding grounds, with loudness and harshness intermediate between T. alba and T. novaehollandiae; cricket-like chirruping by male returning to nest with food, audible only at close range; high sibilant “psseeoo” in flight near nest (perhaps alarm call); another possible alarm near nest is harsh “scaarp, scaarp” by female; also bill-snapping, snoring and high-pitched trilling or wheezing calls by nestlings; nestlings in Thailand gave hissings sounds of constant pitch for c. 1 minute (2).

Breeding

Oct–Mar, mostly Oct–Dec, in India, but once Jul; Sept–Jan in China and Philippines; May–Jun in Papua New Guinea; Feb–Sept in E coastal Australia; at any time of year depending on conditions in inland Australia. Two nests found in NW Thailand on 24 Jan 2008 had nestlings estimated to be 2–3 weeks old (2). Usually solitary, but in favourable conditions sometimes loosely colonial, with nests separated by few hundred metres. Nest on ground in dense grass usually over 1 m high, or in sedges, usually away from trees, but in Australia once below mangrove and recently in young pine plantation; flimsy pad or mat of grasses soon trampled by nesting activity, canopied in grass and with series of (usually three) approach tunnels or pathways, even over shallow water, made by pushing through to nest; entrance to main tunnel flattened by frequent food deliveries. Clutch 4–6 eggs in India, 3–8 in Australia (10), more pearl-shaped than in other Tyto, usually laid at two-day intervals; size range 41–44 mm × 29·8–33 mm (10); incubation 31 days in Australia; natal down white, second (mesoptile) down whitish in Philippines , buffy in China, tawny to buff or golden-brown in Australia; young fledge after c. 2 months, hiding in grass during day and returning to nest at night, and may stay around nesting area for some weeks, at least in Australia.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). CITES II. Rare to very rare throughout most of range, but can be locally common in undisturbed areas or during rodent plagues (e.g. Australia). Strongholds appear to be India, Australia and New Guinea. In Indian subcontinent, described as rare and local or very local, and no recent records from Bangladesh. Much of apparent rarity possibly due to lack of observations or confusion with T. alba, but population declines caused by hunting and habitat loss likely, e.g. in China, Taiwan, Philippines and parts of coastal Australia. In NE Australia, rodenticides used since 1992 to control rats in cane fields have caused local population declines of 75–85%. Patchy distribution indicates possible recent fragmentation, e.g. nominate race and chinensis may have had continuous distribution in S Asia but now separated; it has been suggested that they intergrade W of Vietnam. One of two nests found recently in NW Thailand destroyed by burning, suggesting that seasonal burning is a major threat to successful nesting in that area (2). Also, sufficient similarity between Indian and Australian birds has led to suggestion that the species would be found in Malaysia and W Indonesia, but no known records yet.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding