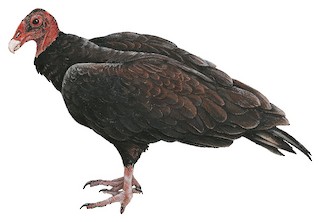

Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Scientific name definitions

Revision Notes

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Basque | Sai indioilarra |

| Bulgarian | Пуйков лешояд |

| Catalan | zopilot capvermell |

| Croatian | crvenoglavi lešinar |

| Czech | kondor krocanovitý |

| Dutch | Roodkopgier |

| English | Turkey Vulture |

| English (United States) | Turkey Vulture |

| Estonian | kalkunkondor |

| Finnish | kalkkunakondori |

| French | Urubu à tête rouge |

| French (Canada) | Urubu à tête rouge |

| German | Truthahngeier |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Malfini karanklou |

| Icelandic | Kalkúnhrævi |

| Japanese | ヒメコンドル |

| Norwegian | kalkunkondor |

| Polish | sępnik różowogłowy |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | urubu-de-cabeça-vermelha |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Urubu-de-cabeça-vermelha |

| Russian | Катарта-индейка |

| Serbian | Ćurkasti lešinar |

| Slovak | kondor morkovitý |

| Slovenian | Puranji jastreb |

| Spanish | Aura Gallipavo |

| Spanish (Argentina) | Jote Cabeza Colorada |

| Spanish (Chile) | Jote de cabeza colorada |

| Spanish (Costa Rica) | Zopilote Cabecirrojo |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Aura tiñosa |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Aura Tiñosa |

| Spanish (Ecuador) | Gallinazo Cabecirrojo |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Zopilote Cabeza Roja |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Zopilote Aura |

| Spanish (Panama) | Gallinazo Cabecirrojo |

| Spanish (Paraguay) | Cuervo cabeza roja |

| Spanish (Peru) | Gallinazo de Cabeza Roja |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Aura Tiñosa |

| Spanish (Spain) | Aura gallipavo |

| Spanish (Uruguay) | Cuervo Cabeza Roja |

| Spanish (Venezuela) | Oripopo |

| Swedish | kalkongam |

| Turkish | Hindi Akbabası |

| Ukrainian | Катарта червоноголова |

Revision Notes

David A. Kirk, Michael J. Mossman, Keith L. Bildstein, Julie M. Mallon, and Adrián Naveda-Rodríguez revised the account. Peter Pyle contributed to the Plumages, Molts, and Structure page. Guy Kirwan contributed to the Systematics page. Neil J. Buckley reviewed the account. JoAnn Hackos, Robin K. Murie, and Daphne R. Walmer copyedited the account. Eliza R. Wein revised the distribution map. Arnau Bonan Barfull curated the media. Gracey Brouillard curated the references.

Cathartes aura (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- CATHARTES

- aura

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

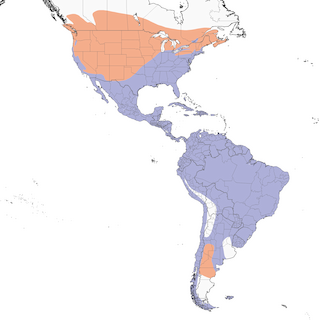

Wheeling sedately over forests, farmland, coasts, deserts, wetlands, and urban areas, the Turkey Vulture is the most migratory and widely distributed vulture in the Americas. This common and familiar species breeds from southern Canada to southernmost South America and several associated islands. Five subspecies are recognized, distinguished by size, plumage, head coloration, geography and migratory patterns. Three North American subspecies are partly migratory, with millions of the western subspecies, meridionalis, migrating to Central and South America, where they coexist with the resident and migratory Turkey Vulturesubspecies and other vulture species. At least some populations of temperate South American subspecies migrate northward to temperate or tropical sites for the austral winter. The species' broad distribution reflects its soaring capabilities and adaptability for nesting, feeding and thermoregulation.

Named after the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) because of its bare, red-colored head, the Turkey Vulture is almost exclusively a scavenger (the genus name Cathartes means “purifier”), and it rarely kills small animals or invertebrates. Most reports of vultures killing livestock in North America are attributable to the more aggressive and closely related Black Vulture (Coragyps atratus) (1). The Turkey Vulture tends to forage solitarily, but individuals attracted to other feeding vultures often congregate at carcasses. Communal Turkey Vulture roosts facilitate group foraging and social interactions. Roosts range in size from a few birds to several thousand, often including Black Vulture, and are sometimes “advertised” by spectacular evening flights.

The highly developed olfactory sense of the Turkey Vulture enables individuals to locate concealed carcasses beneath vegetative cover, including forest canopies. The Black Vulture often follows the Turkey Vulture to food and sometimes displace them at carcasses through sheer numbers; in response, in some areas the Turkey Vulture specializes in small food items that can be eaten quickly.

The Turkey Vulture occurs in almost all land cover types within its geographic range but is particularly common in open country such as farmland with pasture and abundant carrion close to undisturbed forested areas for perching, roosting, and nesting. The species nests in dark recesses beneath boulders, on cliff ledges, and in caves, hollow trees, logs, stumps, brush piles, and abandoned buildings. In addition to being prone to accumulating pesticides and other contaminants, it has a propensity to feed in agricultural and roadside locations, making it vulnerable to accidental trapping, collisions, electrocution, shooting, and the ingestion of lead from animals that have been shot. Its former persecution as a potential vector of livestock disease or as a predator of young animals has largely ceased, since these allegations have proved false. However, the Turkey Vulture sometimes causes damage to human built structures and fatalities due to aircraft collisions. That said, the Turkey Vulture provides irreplaceable supporting and regulating ecosystem services and is a critical component of ”Nature’s clean-up crew", facilitating nutrient flow within food webs, removing carrion from roads and roadsides, and reducing the transmission of infectious diseases (2, 3).

Tolerant of human activity and adaptable in its diet and choice of nest sites, this species has fared well in both natural and human-dominated landscapes; its populations are generally stable or increasing, except for some areas in the western and far southern United States.

The literature on the Turkey Vulture within its northern breeding range is rich, from fascinating early accounts and anecdotes (e.g., 4, 5) to more recent studies and reviews (6, 7, 8, 9). Yet surprisingly little is known about the breeding biology in South and Central America or its ecology in nonbreeding areas (e.g., specific wintering locations for North American subspecies). Because of its social organization and habit of communal roosting, the Turkey Vulture has been the focus of several studies testing whether individuals can learn the location of food from other flock members (10, 11, 12). Its use of home range and foraging habitat has been described quantitatively in southern Pennsylvania and northern Maryland (13), and recently in South Carolina and Georgia (14), but such information is lacking over much of its range in North America. Research in South America suggests that the North American populations compete with the smaller resident subspecies in some parts of its non-breeding range (15, 16, 17, 18). Niche differentiation and resource segregation may be a more widespread phenomenon among migratory or resident vultures. More recent studies have: (1) deployed satellite tracking devices to obtain exciting new information on movement patterns of migratory Turkey Vulture in different parts of its range (western, interior and eastern North America and interior South America (19, 20, 21); (2) demonstrated that stopover sites on migration are used in response to poor weather conditions and less so to replenish food reserves (22); (3) documented monthly variation in home range and core area use using novel methods (23); (4) revealed previously little-known aspects of breeding behavior from Saskatchewan, including age at first breeding (24); (5) documented details of undisturbed nesting behavior (Raptor Resource Project; RRP); and (6) reviewed the vital scavenging role of vultures in providing ecosystem services, in response to the precipitous declines in many other vulture species globally (2).Even though the Turkey Vulture is currently widespread and apparently increasing or expanding its range in many areas, it is subject to many of the same threats as Old World Vultures, which have undergone sudden population declines. It is also a strong bioindicator for other Neotropical vultures, about which little is known (25). Being more abundant and widespread than other Cathartidae (some of which are rare), except for Black Vulture, changes in its numbers can be more closely linked statistically to environmental changes, and it can therefore act as an ‘umbrella’ species.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding

Map last updated 11 October 2023.